Most people who know me well know that I enjoy routine. I like to wake up, exercise, eat my meals, drink my tea, and go to bed at roughly the same time every day. (I prefer exactly the same time, but I’ve matured at least enough to know that that isn’t always feasible.) Every so often, I have to replace a routine that is no longer serving me. And sometimes, I hang onto routines even though I am fully aware they are no longer serving me. But in general, I think my routines do more good than harm.

I was delighted to receive for Christmas from my future in-laws the 2020 weekly edition of The Simplified Planner by Emily Ley. Aside from the fact that it’s pretty and sturdy, has a large format (which means more room for writing), comes with a list of small suggestions for simplifying one’s life, and is part of a lifestyle and paper products brand with an undeniably supportive and cheery vibe, it’s a fairly standard planner. By this, I mean that there aren’t prescripted categories for what to write each day; most of the pages consist simply of dates and blank lines. I know from watching one of Ley’s supportive and cheery videos that this is intentional: She wanted to create a planner that could become what the user needs it to be. And for me, at this season of my life, I’ve discovered that I need to write down and carry around with me a hyperspecific list of what I must do every day and–this is key–what I want to do every day.

I realized that for a long time now–probably years–I’ve been spending my unstructured time wandering around my house feeling the anxiety of all the things I need to do but unsure of what I should do next. This habit has been exacerbated by my current freeform work schedule (I have to be on campus for classes, office hours, and meetings, and that’s it). So even though I believe that part of being a functioning adult is knowing how to use one’s time without having to be told what to do, I have recently felt that I might actually need someone to tell me what to do, at least for a while. And I decided that that person ought to be me.

So I’m filling out every line of my planner. And as I mentioned, these are big pages. I’m not just writing down classes and appointments; I’m also writing down specific times for things like “prayer while making tea,” “have my first coffee,” “talk to Jordan,” “blog,” and “yoga”–things that I say are important (and that I typically enjoy) but that I apparently have never considered important enough to set a time for on my schedule. (This includes those routine items that I mentioned in the first paragraph–yes, I’m writing “wake up” and “go to bed” in my planner.) The level of specificity might seem ridiculous, but judging by these first few weeks of the year, it seems like it’s helping. The true test, of course, will be once my classes really get going and I have grading to do, but I already have a plan for that: one of my to-do items this week is “Count # of students & divide by # of weekdays to schedule grading.” If it’s important, I’m writing it down.

One good thing about this system is that my to-do list is finite and specific to each day, rather than vague and unending, so I’m getting the added benefit of a major list-crossing-off endorphin rush each day. There were one or two days last week when my to-do list was too ambitious, but I was able to move the items to another day or even the following week after re-assessing their urgency.

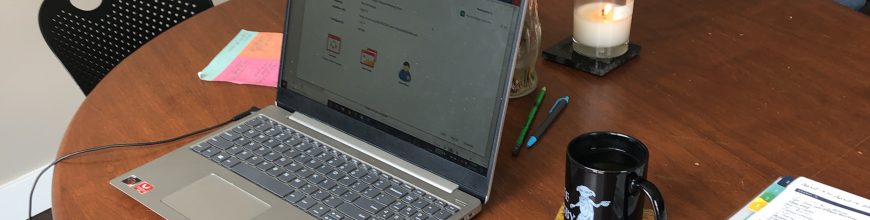

I should also mention the weekly routine I’ve added that, so far, is incredibly helpful: taking an hour each Sunday night to plan my week. (I am grateful to life coach Cindy Sielawa for this suggestion.) I create a calm environment by lighting all the candles I got for Christmas (it’s a lot–guys, I like fire) and doing a facemask (the skincare kind, not the football kind), and then I fill out all those blanks in my planner. And my routine-loving heart is happy.

And you can make it even happier by telling me some of your favorite daily routines and planning habits! Please share in the comments!